From living room to family room: A model for the unhoused population

Occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) may be the key to addressing nonmedical drivers or determinants of health in the unhoused population through wellness promotion and disease prevention. These drivers include housing access, stress management, food insecurity, transportation, health care, and social support (Hoelscher et al. 2024)

AOTA members get more. Join or sign in for access to this resource

Occupational therapy practitioners (OTPs) may be the key to addressing nonmedical drivers or determinants of health in the unhoused population through wellness promotion and disease prevention. These drivers include housing access, stress management, food insecurity, transportation, health care, and social support (Hoelscher et al. 2024) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nonmedical Drivers of Health Factors

Source. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (n.d.).

The occupational therapy profession can build community-based interventions and interdisciplinary partnerships to support the unhoused population. Studies have shown that group occupational therapy interventions improve feelings of autonomy, confidence, and stress reduction (Beker & DeAngelis, 2021; Gutman et al., 2019; Schultz-Krohn et al., 2021). Occupational therapy services also improve ADLs, IADLs, health management, cognition, and time management for unhoused people (Alderdice et al., 2022; Grajo et al., 2020; Synovec et al., 2020).

To address this need, an interprofessional occupational therapy program was established in 2021 in a room aptly referred to as the living room. The Occupational Therapy Living Room (OTLR) services focus on health and wellness management while aligning with the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (4th ed.; American Occupational Therapy Association, 2020).

Services

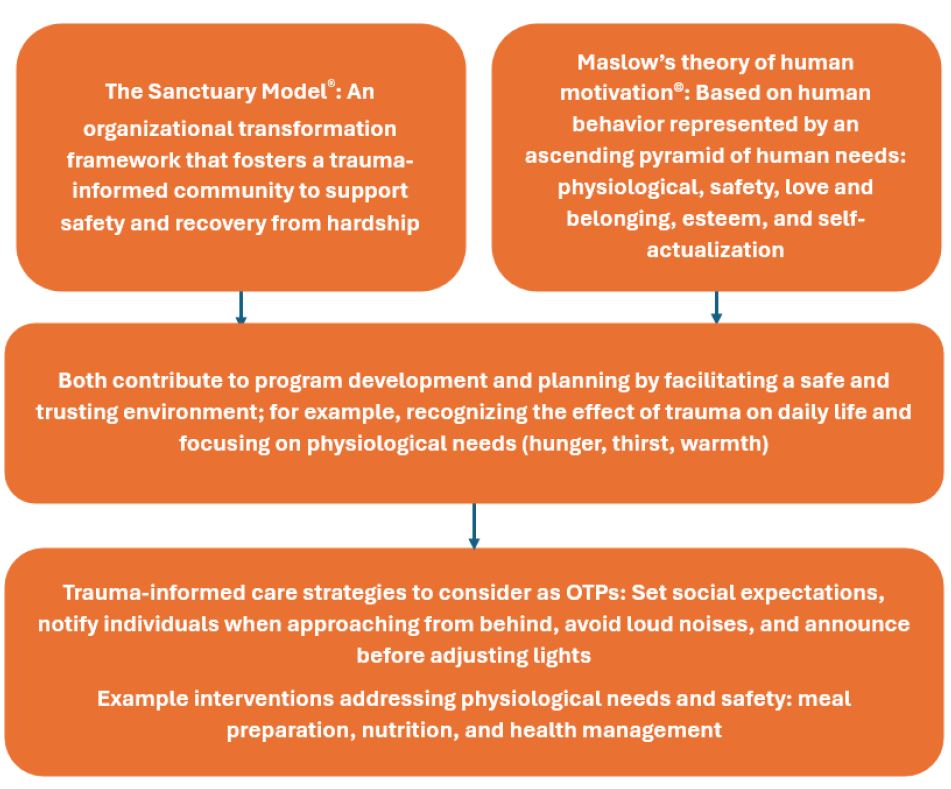

The OTLR program was developed using the Sanctuary Model® (Sanctuary Institute, n.d.) and Maslow’s (1943) theory of human motivation to provide respite, trust, and a sense of belonging (see Figure 2). Collaboration between a university and a nonprofit organization enabled the buyout of occupational therapy faculty time to supervise and provide services, including therapeutic groups and individual sessions led by occupational therapy students.

Figure 2. Application of Frameworks in OTLR

Note. The image describes the application of two perspectives: The Sanctuary Model (Sanctuary Institute, n.d.) and Maslow’s (1943) theory of human motivation to community-based occupational therapy practices. OTLR = Occupational Therapy Living Room.

Therapeutic groups include formal and social groups. Occupation-based formal groups are guided by Cole’s (2025) seven steps following the completion of a needs assessment. Programming addresses nonmedical drivers or determinants of health through employment, IADLs, leisure participation, health management, and sleep. For example, fall 2024 programming targeted social and emotional promotion and health management interventions (see Table 1). Social groups included crafting, do-it-yourself pocket-sized self-care items, and community outings. Participants reporting deriving a sense of belonging from groups and indicated that outings enabled connectedness, dignity, and autonomy (Schultz-Krohn et al., 2021).

Table 1. Fall 2024 Programming for Occupational Therapy Students

|

Group Title |

Purpose |

Outcome Measurements |

|

Navigating Our Wellness

|

Health literacy through symptom and condition management |

Homegrown evidence-based survey measuring perceived understanding and application of health information |

|

Emotional Architects |

Activity-based psychoeducation for social and emotional health promotion and maintenance |

Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983) |

|

Sensing Joy |

Social and emotional health through meaningful, health-promoting habits and routines |

Engagement in Meaningful Activity Scale (Goldberg et al., 2002) |

|

Mind Over Muscles |

Social and emotional health through physical activity and education |

Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995) |

Drop-in consultations and recurrent sessions address individualized needs. In recurrent sessions, an occupational profile and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (Law et al., 2019) help participants identify occupational challenges and set goals. Goals commonly target employment acquisition, computer literacy skills, and emotional regulation (DeAngelis et al., 2019).

Participant Testimonials

Participants’ feedback revealed that OTPs and occupational therapy students foster mutual respect for participants, are nonjudgmental, and engage in active listening. These attributes facilitate building therapeutic relationships and fostering trust between the unhoused population and health care providers and systems. As a result, the OTLR has become a reliable place to feel seen, heard, and valued. A participant stated, “You make us feel heard when people don’t usually listen to us… You all help us feel like we’re achieving something” (Sosa et al., 2024, p. 88).

The value occupational therapy brings to the unhoused population is diverse and long-lasting. Participants reported improvements in functional mobility, use of assistive devices, and joint mobility. Other critical benefits are social participation, occupational identity, and mental health. Participants described the OTLR as a safe place to relax with peers, have fun, and express themselves. The OTLR team recognized the prevalence of occupational deprivation and strived to create opportunities to return to meaningful occupations or explore novel ones. One participant shared, “Before occupational therapy I hated myself. I learned to value myself and identify qualities I like about my personality” (Sosa et al., 2024, p. 78). One participant recently engaged in resume writing in preparation for an employment opportunity. Sharing his anxiety related to the onsite interview due to past incarceration and gaps in employment, he engaged in mock interviews and “dress for success” sessions. He also made personalized DIY scented cologne for his interview day. As a result, he felt empowered, securing employment which allowed him to save for an apartment. He provides the OTLR with ongoing updates and credits OT for his success.

Interprofessional Collaborations

The OTLR takes place in a nonprofit day services program called the Hub of Hope (Hub). The Hub serves unhoused individuals, many of whom have a serious mental illness or substance use disorder, or both. Individuals can access daily showers, laundry services, meals, case management, transportation to shelters, occupational therapy, medical care, and toiletries (Project HOME, n.d.). Interprofessional collaboration is integral to the Hub’s operations and contributes to comprehensive care to support sanctuary. Partnerships include those within the Hub (see Table 2), academic universities (see Table 3), and community organizations that volunteer their efforts to meet the needs of the unhoused population (see Table 4).

Table 2. Internal Hub Partnerships

|

Collaborations |

Purpose |

|

Adult education and employment services |

No-cost education, vocational training, and employment services |

|

Case management |

Housing assessments and community resources support |

|

Hospitality services |

Laundry, hygiene, showers, meals, and clothing services |

|

Medical clinic |

Medical staff to enhance health management; collaborates with OTLR via participant referrals |

|

Advocacy team |

Occupational injustice shared with local and state government officials |

|

Program directors |

Supervision and coordination of services; conflict resolution to ensure respect and safety |

|

Security |

De-escalation and conflict resolution |

Note. OTLR = Occupational Therapy Living Room.

Table 3. Academic Partnerships

|

Collaborations |

Purpose |

|

Emergency department unsheltered disposition planning |

Urban hospital interprofessional collaboration to ensure optimal care/disposition for unhoused individuals |

|

Medical students |

Symptom and condition management; building trust with medical providers |

|

Occupational therapy students |

Promotion of occupational justice with a holistic approach to population health |

|

Physical therapy students

|

Health management through foot care, balance, and functional mobility education |

|

Effect on university community |

Health and wellness partnerships to address occupational injustice |

Table 4. Community Partnerships

|

Collaborations |

Purpose |

|

Animal-assisted therapy |

Social and emotional health promotion through a certified emotional support dog and trained handler |

|

City public health education programs |

Health literacy and management |

|

Community menders |

Sewing repair for clothing |

|

Dance classes |

Promotion by OTP volunteer of physical activity, social participation, and health promotion |

|

Legal clinic |

No-cost legal services for all low-income individuals with disabilities, such as tenant rights & responsibilities sessions |

|

Licensed massage therapy |

Therapeutic modality to address mental health and physical disabilities, including chronic pain and arthritis |

|

Mural arts program |

Vocational art training program that promotes employment acquisition |

|

PA ABLE |

Pennsylvania state-funded financial management resources for those receiving government assistance |

|

TechCycle project |

Access to refurbished, no-cost laptops |

|

Public health students |

Education on voter rights and public health |

|

Osteopathic medicine students |

Social and emotional health promotion through grief, trauma, and loss groups |

|

Soul2Sole Bounce Fitness |

Trauma-informed engagement in physical activity |

|

Travel training program |

Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority OTPs: community mobility education and training |

|

TechOWL |

A program of Temple University providing no-cost, gently used adaptive equipment/assistive devices |

|

Vetri Community Partnership |

Medicinal nutrition and meal preparation led by culinary experts |

Note. OTP = occupational therapy practitioner; TechOWL = Technology for Our Whole Lives.

Conclusion

Collaborative, evidence-based, OTP-developed and OTP-directed programs are keystones in the movement toward a more compassionate and hopeful future for the unhoused population. With more than 5,000 individual participant visits in the 2024-2025 timeframe, the OTLR is an example of a program committed to this movement and can be replicated by future OTPs and occupational therapy students who have an unwavering dedication to this cause. The first step in creating such programs is simple and yet profound: providing a welcoming and accepting sanctuary for those who are often left behind.

References

Alderdice, E., Wolfe, D., Timmer, A. J., & Unsworth, C. A. (2022). Use of the AusTOMs–OT to record outcomes in an occupational therapy homeless service. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 85, 669–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/03080226211067427

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Beker, J., & DeAngelis, T. M. (2021). Life skill development and its impact on perceived stress, employment and education pursuits: A study of young adults with a history of homelessness and trauma. Student Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.46409/001.xvoh2735

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Cole, M. B. (2025). Group dynamics in occupational therapy: The theoretical basis and practice application of group intervention (6th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003524403

DeAngelis, T., Mollo, K., Giordano, C., Scotten, M., & Fecondo, B. (2019). Occupational therapy programming facilitates goal attainment in a community work rehabilitation setting. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 6, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-018-00133-5

Goldberg, B., Brintnell, E. S., & Goldberg, J. (2002). The relationship between engagement in meaningful activities and quality of life in persons disabled by mental illness. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 18, 17–44. https://doi.org/10.1300/J004v18n02_03

Grajo, L. C., Gutman, S. A., Gelb, H., Langan, K., Marx, K., Paciello, D., … Teng, K. (2020). Effectiveness of a functional literacy program for sheltered homeless adults. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 40, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449219850126

Gutman, S. A., Barnett, S., Fischman, L., Halpern, J., Hester, G., Kerrisk, C., … Wang, H. (2019). Pilot effectiveness of a stress management program for sheltered homeless adults with mental illness: A two-group controlled study. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 35, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212x.2018.1538845

Hoelscher, D. M., van den Berg, A. E., Roebuck, A., Flores-Thorpe, S., Menendez, T., Andrulis, S., & Hunt, E. T. (2024). Non-medical drivers of health [Report]. UTHealth Houston School of Public Health. https://sph.uth.edu/research/centers/dell/legislative-initiatives/tx-rpc-project-reports/Non-Medical%20Drivers%20of%20Health_Update%202024.pdf

Law, M., Baptiste, S., Carswell, A., McColl, M., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. (2019). Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (5th ed., rev.). COPM, Inc.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

Project HOME. (n.d.). Hub of Hope. https://www.projecthome.org/hub-hope

Sanctuary Institute. (n.d.). Sanctuary model. https://www.thesanctuaryinstitute.org/about-us/the-sanctuary-model/

Schultz-Krohn, W., Winter, E., Mena, C., Roozeboom, A., & Vu, L. (2021). The lived experience of mothers who are homeless and participated in an occupational therapy leisure craft group. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 37, 107–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212x.2021.1881022

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-Nelson.

Sosa, A., Erie, B., Johnson, N., Jones, S., & DeAngelis, T. (2024). The complexities of serious mental illness, homelessness, and functional cognition: An occupational therapy perspective [Doctorate of Occupational Therapy Program capstone presentation, Thomas Jefferson University] (Publication No. 70). Jefferson Digital Commons. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/otdcapstones/70/

Synovec, C. E., Merryman, M. B., & Brusca, J. (2020). Occupational therapy in integrated primary care: Addressing the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness. Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 8, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1699

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Social determinants of health. Healthy People 2030. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

Allie Ward, OTD, is a graduate of Thomas Jefferson University and completed her doctoral capstone at the Hub of Hope, in Philadelphia, PA.

Samantha Carney, OTD, is a graduate of Thomas Jefferson University and completed her doctoral capstone at the Hub of Hope.

Emily Garron, OTD, is a graduate of Thomas Jefferson University and completed her doctoral capstone at the Hub of Hope.

Morgan Cepollina, OTD, is a graduate of Thomas Jefferson University and completed her doctoral capstone at the Hub of Hope.

Tina DeAngelis, EdD, MS, OTR/L, FAOTA, is a Professor at Thomas Jefferson University's College of Rehabilitation Sciences, and Director of Occupational Therapy Services at the Hub of Hope.