Checklist of Community Mobility Skills: Connecting Clients to Transportation Options

Connecting transportation options with client functional skills is an important occupational therapy contribution to client safety and sustainable community mobility, particularly when the need for transportation alternatives comes in response to a medical event or a deteriorating health condition. Driving is and will continue to be the preferred method of community mobility for older adults, especially for the majority of older adults who live in suburban and rural communities (Rosenbloom, 2012). However, driving lifetimes are finite. More than 6,000,000 individuals over the age of 70 stop driving each year, with older adults outliving their driving abilities by some 6 to 10 years (Foley et al., 2002).

Because community mobility is critical for maintaining physical and mental health and quality of life (Dickerson et al, 2019; O’Neill et al., 2019) and essential as a means to engage in activities outside the home to support social participation (Choi et al., 2014), it is important to assist older adults and/or medically-at-risk drivers (i.e., drivers, regardless of age, whose medical condition puts them at risk for driving) with selecting and accessing alternative means of transportation. In fact, in a recent commentary, O’Neill and colleagues (2019) introduced the importance of transportation equity as a public health issue, encouraging professionals in health care and transportation to work together to develop transportation mobility throughout the life span.

Because driving and community mobility is an IADL and well within our scope of practice, occupational therapy practitioners must respond and be part of the solution to support transportation equity for our clients, as clearly articulated in Vision 2025, “through effective solutions that facilitate participation in everyday living” (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2017).

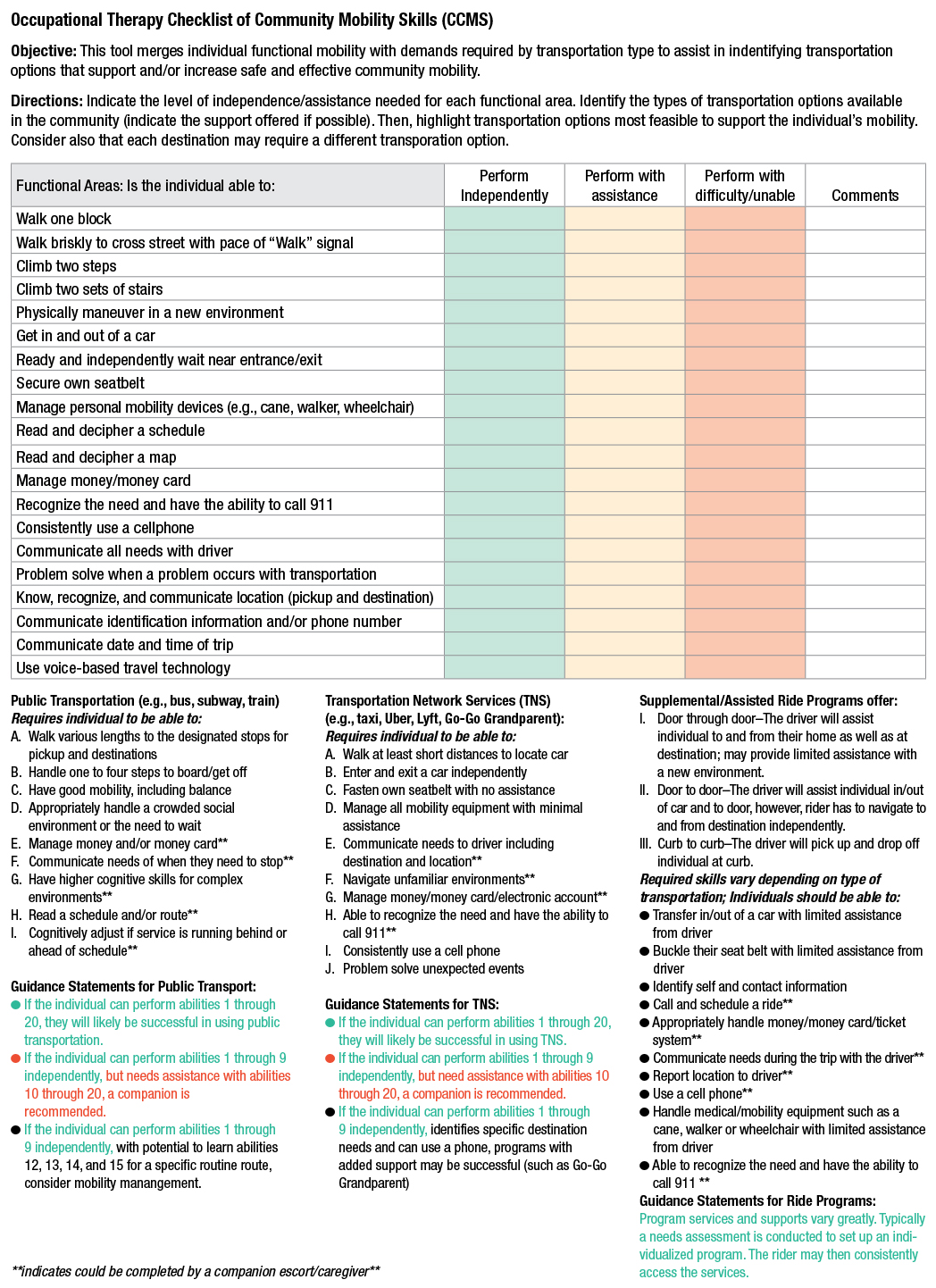

In addition to improving functional mobility in the home, occupational therapy practitioners must assist in facilitating community mobility for clients so they can go beyond their front door to participate in their community and social environments. This is true for all clients, whether the need to cease driving is temporary (during recovery) or long term. To that end, we developed an Occupational Therapy Checklist of Community Mobility Skills (CCMS) as a resource for occupational therapy practitioners to address a “gap,” or missing piece, when considering community mobility options with clients who have impairments.

For many clients and practitioners alike, the use of public or private transportation services is unfamiliar. In conjunction with recommending an individual not drive, practitioners need to understand and convey the supports and barriers their clients may face when selecting from the available transportation options. In identifying clients’ strengths and weaknesses, practitioners can than assist in appropriate matching to support and/or increase safe community mobility.

Transportation Options

Kerschner and Silverstein (2018) identified five general options in the Transportation Family that may be available in a community: Community Transit, Public Transit, ADA Paratransit, Ride Hailing Services, and Volunteer Driver Programs. Community transit is a general term for a complete range of transportation (Kerschner & Silverstein, 2018). Public transit includes publicly funded transportation systems serving the general public, such as buses, subways, rail, or ferries. The American with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) requires communities that have fixed bus routes or rails to also provide complementary services for individuals with disabilities who cannot use public transit (i.e., ADA paratransit).

Ride hailing services include for-hire vehicles such as taxi services and limousines, and on-demand transportation services such as Uber and Lyft. These are included under the umbrella term transportation network services (TNS). Lastly, most communities have at least a few volunteer driver programs that provide transportation for specific populations, often emphasizing older adult passengers. Whereas larger communities have a mixture of all of these services, many small, mostly rural communities are fortunate if they have one or two volunteer driving programs to meet the needs of their older adult population. The complexity of using any of these systems for medically-at-risk drivers, who are generally only familiar with driving their own vehicles, can be overwhelming.

In our health care system, social workers or case managers are traditionally tasked with finding housing and transportation as discharge approaches. Typically, in discharge planning, occupational therapy practitioners, as well as other team members, provide their expert opinions about clients’ functional abilities in terms of the living environment. Can they live independently, do they need supervision, or is assistive living or long-term care the best or least restrictive option? Less frequently, the case manager seeks information about community mobility beyond planning the trip home if the client is using a wheelchair.

If the occupational or physical therapist doesn’t offer advice about the client’s functional limitations in transportation, the case manager may not offer more than a list of bus routes or ADA transport numbers. This option may get the client back and forth to their medical appointments but offers little to enhance social participation.

The complexity of selecting transportation options for an adult with cognitive impairment who is does not have a physical impairment is not always apparent. For this at-risk population, occupational therapy practitioners have the opportunity to apply their expert knowledge of functional capacities to describe the supports needed for the client’s successful negotiation of the environmental complexities of community mobility. Thus, the CCMS was developed to support occupational therapy practitioners who may not be familiar with the details of transportation systems and/or the specific skills, abilities, and knowledge needed to negotiate the array of transportation options.

Description and Directions

The CCMS was designed for the occupational therapy practitioner as a therapeutic intervention planning tool. It was crafted in conjunction with OT-DRIVE (Schold Davis & Dickerson, 2017), which offers a framework to generally classify client factors through the easily identifiable colors of green (primarily intact skills), yellow (impairments, degree of impact on driving short or long term is unclear), and red (moderately to severely impairment). This framework enhances understanding and communication between practitioners, medical team members, clients, and family members.

The CCMS has two parts. In the first section, the CCMS identifies 20 person/client factors that may be required of the individual to meet the demands of three major types of transportation options. Approximately half are physical factors (bolded), and the other half are cognitive factors. Based on an occupational therapist’s knowledge of the client, obtained through the evaluation and intervention processes, practitioners would indicate the level of assistance needed as:

Green: Able to perform independently

Yellow: Able to perform with assistance

Red: Unable to perform; performs with difficulty even with assistance

The second part of the CCMS divides transportation options into three levels of service: public transportation (e.g., bus, subway, train, airlines), transportation network services (e.g., taxis, ride hailing), and the specialized services or assisted ride programs. Individuals requiring transport while seated in a wheelchair may be referred to accessible transit, paratransit services, or driving rehabilitation. For each category, the CCMS lists specific client factors. Aspects requiring a family member or escort are identified by asterisks. In addition, guidance statements are offered to assist practitioners in discussing community mobility. (Note: Local programs could be added following the same pattern.)

Specific Directions

1. Indicate the level of independence/assistance needed for each of the 20 functional areas or skills based on client factors understood through evaluation and/or intervention processes.

2. Consider both strengths and weaknesses to determine the least restrictive general type of transportation options (e.g., public, TNS, or assisted ride programs) that are appropriate, safe, and convenient for the client.

3. Using knowledge of the client’s home community and the guidance statements, identify the specific options and rationale to be discussed with the client, family member(s), and/or social worker or case manager.

Intervention Options. Occupational therapy practitioners offer person-centered intervention. When instructing clients that driving is not an option, now or in the future, practitioners should pair this directive with guidance and support to maintain community mobility (i.e., social participation) as a non-driver. Families as well as clients appreciate learning strategies for how the individual will get around. Most important, practitioners must help clients interpret transportation options functionally, beyond providing a generic list of bus routes or taxi services. Just as an occupational therapist would not simply offer a list of dressing options for a client with hemiparetic arm but in fact work with the client to problem solve the best method to dress (e.g., shoes without ties), by using the CCMS to identify appropriate transportation options, practitioners could explain how a city bus may not be a safe choice because of mobility limitations or memory concerns.

Compliance and follow through are additional barriers to successful community mobility. The client and family may need to understand why a more costly option of taxi or escorted transportation would be their safest option. The CCMS helps practitioners translate the known concerns leading to the recommendation to not drive, to the selection of the most appropriate and safe transportation options while including a structure for communication and education between practitioners, clients, and their families.

Considerations. The CCMS may seem simple, but it requires a skilled occupational therapy practitioner with a thorough understanding of client factors, environmental contexts, and activity analysis to complete the table; apply it to the three categories; and most important, effectively identify the safest options from the array of services that may be available in the community. Cost, eligibility, on-demand access, and support are factors to be considered for each individual. The lower cost for paratransit may be a priority for some, whereas the flexibility of on-demand services may be highly desired by others.

Complementary Resources

A complementary resource for clients and families facing transition to community mobility options is the interactive Transportation Planning Tool located on the occupational therapy–developed website Plan for the Road Ahead (planfortheroadahead.com). Using this tool as an intervention strategy, clients and occupational therapy practitioners can further explore destinations the client needs and wants to access, beginning the process to problem solve strategies for getting there. The cost of using transportation options is a common barrier. This website includes a useful calculator exercise to illustrate how much savings might be available for alternative transportation compared with the cost of owning and maintaining a car.

Conclusion

Transportation equity (O’Neill et al., 2019) will only increase as a public health issue as the U.S. population ages, given that those over the age of 80 are the fastest growing age group. The transportation needs of this aging cohort have been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, most obviously when considering the effects of social isolation on those with mobility restrictions. Older adults without the ability to drive and with limited social contacts are at far greater risk for not getting even basic needs met than the rest of the population. In fact, the outcomes of the pandemic may further confirm the importance of social participation in the community to a person’s well-being. Accordingly, occupational therapy has the unique opportunity to respond to driving and community mobility concerns by offering person-centered solutions. The CCMS tool empowers practitioners to support non-drivers in their continued safe mobility and participation.

Note: The development of the original “Transportation Checklist” was initiated as a clinical doctorate project of Jordyn L. Deppe, OTD, OTR/L under the mentorship of Dr. Debra Gibson of Belmont University with Elin Schold Davis and Anne Dickerson as part of the Older Driver Initiative. Through the AOTA/National Highway Traffic Safety Administration collaboration, the original checklist evolved to the current form of the CCMS. We thank Jordyn for her contribution to the final product.

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2017). Vision 2025. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71, 7103420010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.713002

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. 101-336, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101–12213 (2000).

Choi, M., Lohman, M. C., & Mezuk, B. (2014). Trajectories of cognitive decline by driving mobility: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29, 447–453.

Dickerson, A. E., Molnar, L. J., Bédard, M., Eby, D. W., Berg-Weger, M., Choi, M., … Silverstein, N. (2019). Transportation and aging: An updated research agenda for advancing safe mobility among older adults transitioning from driving to non-driving. The Gerontologist, 59, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx120

Foley, D. J., Heimovitz, H. K., Guralnik, J. M., & Brock, D. B. (2002). Driving life expectancy of persons aged 70 years and older in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 1284–1289.

Kerschner, H., & Silverstein, N. M. (2018). Introduction to senior transportation: Enhancing community mobility and transportation services. Taylor and Frances Group.

O’Neill, D., Walshe, E., Romer, D., & Winston, F. (2019). Transportation equity, health, and aging: A novel approach to healthy longevity with benefits across the life span. NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/201912a

Rosenbloom, S. (2012). The travel and mobility needs of older persons now and in the future. In J. Coughlin & L. D’Ambrosio (Eds.), Aging America and transportation (pp. 39–54). Springer.

Schold Davis, E., & Dickerson, A. (2017). OT-DRIVE: Integrating the IADL of driving and community mobility into routine practice. OT Practice, 22(13), 8–14. https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/Secure/Publications/OTP/2017/OTP-Volume-22-Issue-13-drivers-education.pdf

Anne Dickerson, PhD, OTR/L, SCDCM, FAOTA, FGSA, is a Professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at East Carolina University, in Greenville, North Carolina.

Elin Schold Davis, OTR/L, CDRS, FAOTA, is AOTA’s Practice Manager for Community Access & Driver Initiatives.

For More Information

Driving & Community Mobility Resources

AOTA Online Course: Driving and Community Mobility for Older Adults: Occupational Therapy Roles, Revision

S. Pierce & Davis, 2010. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association. Earn .6 AOTA CEUs (7.5 NBCOT PDUs, 6 contact hours). $180 for members, $257 for nonmembers. Order #OL33.

AOTA Self-Paced Clinical Course: Driving and Community Mobility: Occupational Therapy Strategies Across the Lifespan

M. McGuire & E. Davis, 2012. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association. Earn 2 AOTA CEUs (25 NBCOT PDUs, 20 contact hours). $60 for members, $80 for nonmembers. Order #3031.

Driving Simulation for Assessment, Intervention, and Training: A Guide for Occupational Therapy and Health Care Professionals

S. Classen, 2017. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press. $79 for members, $112 for nonmembers. Order #900389. Ebook: $59 for members, $92 for nonmembers. Order #900416.